This document provides a detailed methodological description of the procedures implemented in the Double Star Calculator. It is intended to serve as a technical reference for users of the Double Star Calculator.

The Double Star Calculator derives a comprehensive set of astrometric and kinematic quantities for individual double star systems, including angular and spatial separations, position angles, proper motion vectors, distance estimates, tangential and spatial velocities, and derived physical parameters such as absolute magnitudes, luminosities, and mass estimates. All computations are based on established geometrical relations, classical error propagation using partial derivatives, and standard astronomical conventions. The mathematical formulations underlying each calculation are documented to ensure transparency, reproducibility, and independent verification of the results.

This section describes the core astrometric and kinematic computations performed for double star systems and stars. These calculations form the basis of the physical interpretation and are directly used in analyses.

The angular separation and position angle (PA) are derived from the Gaia source positions. For the uncertainty estimation, the following conditions apply:

This chapter describes the mathematical formulation used to compute the angular separation (ρ) between two stellar components based on Gaia astrometric data.

To calculate the angular separation θ between two celestial objects based on their Gaia DR3 equatorial coordinates (α1, δ1) and (α2, δ2), the Haversine Formula is used. This method is numerically superior to the Spherical Law of Cosines for small angular distances, as it avoids precision loss when the cosine of a small angle approaches 1. The calculation is performed in radians using the following steps:

The final angular separation is derived using the atan2(y, x) function instead of asin(sqrt(a)). The atan2 implementation is preferred because it is better conditioned for all angles and avoids potential domain errors due to floating-point rounding.

The uncertainty of the separation was derived using first-order Gaussian error propagation, assuming uncorrelated uncertainties in right ascension and declination:

This function computes the position angle θ of a double star measured from North towards East (0°–360°), based on Gaia DR3 coordinates of the two components.

The position angle θ is calculated using the arctangent of the differential coordinates, where atan2(y, x) denotes the quadrant-correct two-argument arctangent, ensuring the correct quadrant of the position angle.

The resulting angle is converted to degrees and shifted to the range 0°–360°.

The uncertainty σθ is calculated using first-order Gaussian error propagation, based on the partial derivatives of atan2:

Where xi ∈ {αA, δA, αB, δB}

This function calculates the spatial separation between two stars in parsecs, using their distances and angular separation. It also computes the uncertainty of the spatial separation via error propagation.

where and are the distances to the two stars and is their angular separation in radians.

The uncertainty of the spatial separation is calculated using partial derivatives:

This function calculates the Parallax Significance Indicator, often referred to as the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR) or the Reliability Index (RI) of the 3D separation. It quantifies whether the observed difference in parallaxes between two stars is statistically significant or merely a result of measurement uncertainties.

A high significance indicates that the stars are physically located at different distances, whereas a low significance (noise) suggests that the stars could be at the same distance within their measurement errors. The indicator is calculated by dividing the absolute difference of the parallaxes by the combined standard deviation (quadratic sum of the individual errors):

Classification Thresholds:

The Parallax Significance Indicator is mapped to qualitative labels to simplify the interpretation of the 3D data:

| Parallax Significance (σ) | Label | Reliability | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 ≤ σ < 3 | LOW | Noise | The distance difference is not statistically significant. Difference is within measurement error. 3D separation is unresolved. |

| 3 ≤ σ < 5 | MED | Moderate | Difference is likely real, but the 3D distance carries significant uncertainty. |

| σ ≥ 5 | HIGH | Significant | Highly significant difference. Stars are clearly located at different depths. |

Example:

Spatial Separation (pc) : 38.97 ± 2.42 pc Spatial Separation (ly) : 127.10 ± 7.90 ly Parallax Significance : 13.09 sigma Distance Reliability : HIGH Significant

This function performs a kinematic analysis of a single star based on Gaia astrometric data. It derives the direction and magnitude of the proper motion vector, the tangential velocity, and, if available, the total space velocity including the radial component. All quantities are accompanied by uncertainty estimates.

The position angle of the proper motion vector is calculated relative to the north direction, measured counterclockwise from north through east (0°–360°). The quadrant-correct two-argument arctangent is used.

Here, and

denote the proper motion components in right ascension and declination, respectively. The function atan2(y, x) ensures correct quadrant assignment.

The uncertainty of the proper motion angle is estimated using a first-order approximation based on the relative uncertainties of the proper motion components. This approach provides numerically stable results for typical Gaia data but does not represent a full analytical error propagation of the atan2 function.

The total proper motion is calculated as the magnitude of the proper motion vector:

The tangential velocity is derived from the total proper motion and the parallax:

The numerical factor 4.74057 converts proper motion in milliarcseconds per year and distance in parsecs into velocity in km s−1.

By default, the Radial Velocity is retrieved from the Gaia DR3 record. If this data is missing, the Double Star Calculator automatically queries the SIMBAD database as a fallback. In this case, the field is labeled Radial Velocity (Simbad) and includes the corresponding Bibcode to identify the original scientific publication and its precision. If a Radial Velocity measurement is available, the total space velocity is computed as:

This chapter describes the CPM evidence algorithm, which utilizes Gaia data to calculate evidence factors. It evaluates systems by contrasting the traditional Harshaw rPM (2D) algorithm with the CPM Evidence Indicator (3D) of the Double Star Calculator.

The Harshaw method (JDSO Vol. 12 No. 4 April 22, 2016, Richard W. Harshaw, CCD Measurements of 141 Proper Motion Stars: The Autumn 2015 Observing Program at the Brilliant Sky Observatory, Part 3) focuses on the ratio of Proper Motion (rPM), a dimensionless quantity comparing the angular velocity difference to the maximum magnitude. It is robust against distance uncertainties but ignores depth (parallax) and radial motion.

| Indicator Type | Threshold | Classification |

|---|---|---|

| Harshaw rPM | < 0.2 | CPM (Common Proper Motion) |

| Harshaw rPM | 0.2 - 0.6 | SPM (Similar Proper Motion) |

| Harshaw rPM | > 0.6 | DPM (Distinct Proper Motion) |

This approach converts observed angular motion and radial velocity into a unified 3D velocity vector in km/s. By utilizing the parallax (

This equation calculates the 3D relative velocity magnitude including the error between two stars by combining their tangential (dvra, dvdec) and radial (dvr) velocity differences. The weighting factor (wr) acts as a binary toggle (1.0 or 0.0), allowing the formula to seamlessly switch between a full 3D space velocity and a 2D transverse velocity depending on data availability. For details refer to chapter 3D Velocity Difference.

The core algorithm uses a variance-summation model. The Evidence Indicator "E" is defined by a Gaussian kernel multiplied by a normalization pre-factor that accounts for the relative weight of the measurement uncertainty.

Normalization Pre-factor: This term term of the equation above acts as a data-quality weight. It has two critical functions:

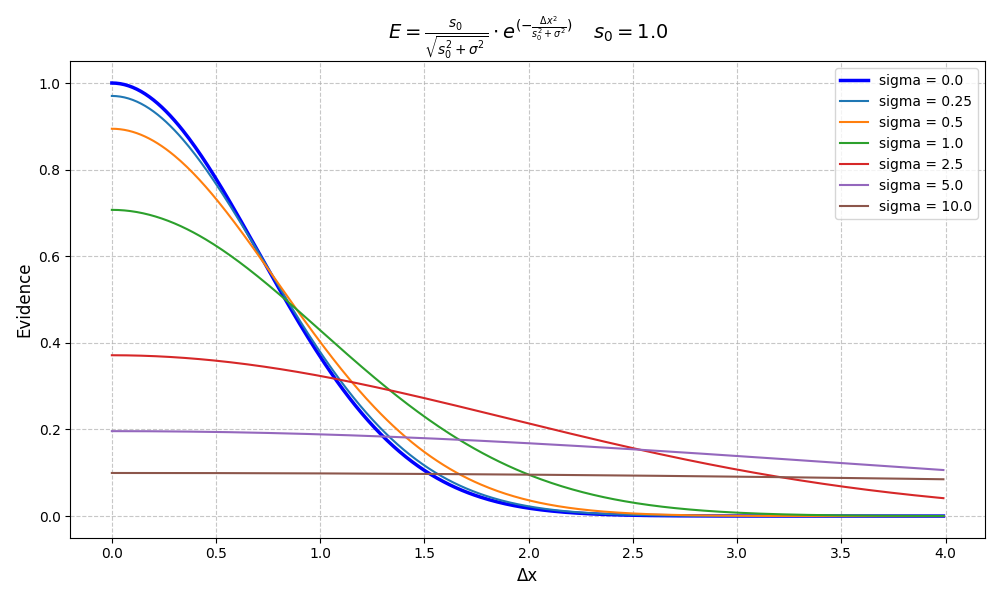

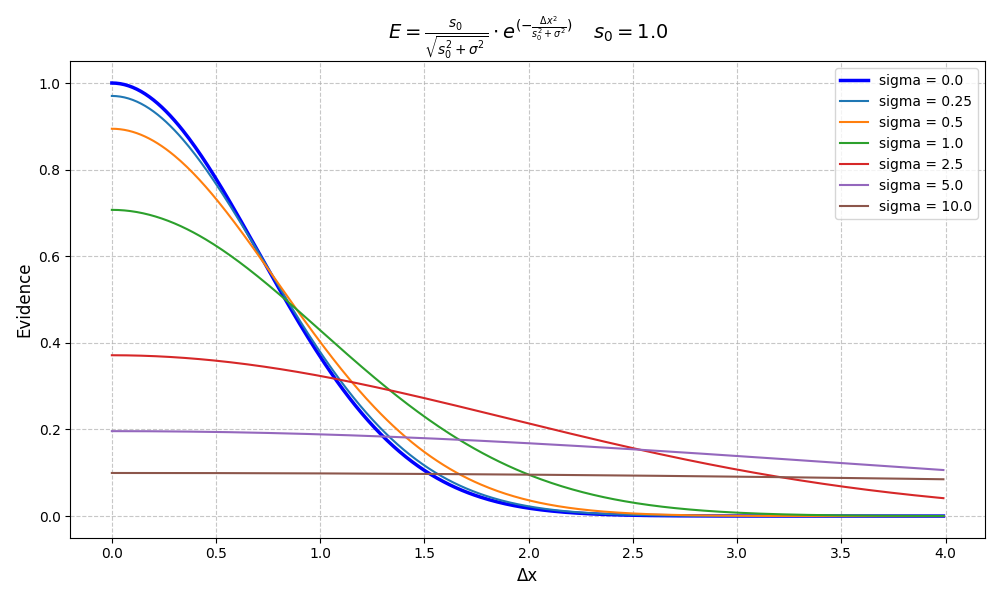

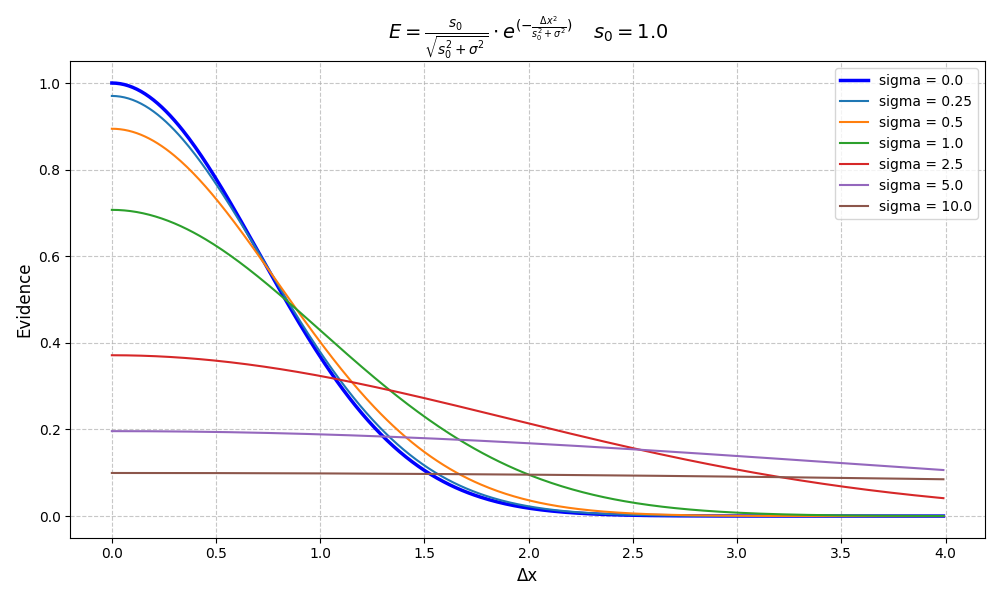

This plot demonstrates how the Likelihood Estimator adapts to varying levels of data quality while keeping the scale factor constant (s0 = 1.0).

Note: An increasing σ not only lowers the peak (Data Quality Weighting) but also broadens the distribution, meaning that at high uncertainty levels, the estimator becomes less sensitive to small changes in Δx.

A specialized version of the Uncertainty-Weighted Likelihood Estimator is used to calculate the Velocity Evidence Indicator. It evaluates the kinematic consistency of a pair by analyzing relative velocities while accounting for physical constraints and data quality.

To maintain reliability in the presence of measurement noise, the algorithm monitors the Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR):

The scale factor v0 determines the tolerance of the likelihood curve. The algorithm distinguishes between two search modes:

To assist in the interpretation of the numerical results (ranging from 0.0 to 1.0), the Velocity Evidence Index is categorized into four qualitative labels:

| Evidence Index | Label | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7 – 1.0 | Strong | High probability of physical association (CPM or Binary). |

| 0.3 – 0.7 | Moderate | Potential association; data supports kinematic similarity. |

| 0.1 – 0.3 | Weak | Low kinematic agreement; likely a chance alignment. |

| < 0.1 | Unlikely | Significant velocity discrepancy; association improbable. |

The CPM Agreement metric cross-references the traditional 2D proper motion classification (according to Harshaw) with the calculated 3D Kinematics Evidence. It identifies whether the 3D spatial and kinematic data support or contradict the classic rPM (proper motion ratio) estimation.

| Harshaw Class (rPM) | CPM Evidence Index (E) | Agreement Level | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| CPM (Common) |

0.75 ≤ E ≤ 1.00 | High | Full 3D confirmation of the CPM status. |

| 0.50 ≤ E < 0.75 | Moderate | Strong support for physical association. | |

| 0.25 ≤ E < 0.50 | Low | 3D data suggests possible discrepancy. | |

| 0.00 ≤ E < 0.25 | Discrepant | Kinematics appear similar in 2D, but 3D data precludes physical association. | |

| SPM (Similar) |

0.50 ≤ E ≤ 1.00 | High | 3D data upgrades or confirms the statistical likelihood. |

| 0.25 ≤ E < 0.50 | Moderate | Both methods indicate a marginal or uncertain association. | |

| 0.00 ≤ E < 0.25 | Discrepant | 3D evidence contradicts the suspected similarity. | |

| DPM (Different) |

0.75 ≤ E ≤ 1.00 | Discrepant | Harshaw sees different motion, but 3D data suggests a strong link. |

| 0.50 ≤ E < 0.75 | Low | Partial contradiction of the DPM status. | |

| 0.25 ≤ E < 0.50 | Moderate | Both indicators suggest a lack of strong physical binding. | |

| 0.00 ≤ E < 0.25 | High | Agreement: Both methods confirm no physical association. |

The Distance Evidence Indicator utilizes a specialized version of the Uncertainty-Weighted Likelihood Estimator to evaluate the spatial proximity of a stellar pair. By analyzing geometrical consistency and relative distance while accounting for physical constraints and data quality, it provides a robust measure of whether two stars are truly co-located.

The reliability of the 3D distance calculation depends heavily on the quality of the parallax measurements. The algorithm dynamically selects the most robust metric:

Depending on the selected type (CPM, Binary), the algorithm switches its internal scale factor (s0) and units to match the expected physical dimensions:

Similar to the kinematic assessment, the Distance Evidence Index is mapped to qualitative labels to provide a quick interpretation of spatial consistency:

| Evidence Index | Label | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7 – 1.0 | Strong | Excellent spatial agreement; the pair is clearly co-located. |

| 0.3 – 0.7 | Moderate | Good spatial agreement; consistent with a common origin or group. |

| 0.1 – 0.3 | Weak | Marginal spatial agreement; distance difference is significant. |

| < 0.1 | Unlikely | Significant spatial discrepancy; co-location is improbable. |

| Evidence Index | Label | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7 – 1.0 | Strong | Excellent spatial agreement; the pair is clearly co-located. |

| 0.3 – 0.7 | Moderate | Good spatial agreement; consistent with a common origin or group. |

| 0.1 – 0.3 | Weak | Marginal spatial agreement; distance difference is significant. |

| < 0.1 | Unlikely | Significant spatial discrepancy; co-location is improbable. |

The kinematic and spatial results are synthesized into a single, unified metric. This provides a final assessment of the physical association between two stars. The total evidence is calculated using the geometric mean of the Velocity Evidence (Evelocity) and the Distance Evidence (Edistance):

The resulting index serves as the final "Confidence Score" for the pair's Common Proper Motion (CPM) or Binary status:

| Total Evidence | Final Label | Physical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| 0.7 – 1.0 | Strong | High confidence pair; kinematic and spatial data are fully consistent. |

| 0.3 – 0.7 | Moderate | Likely association; supported by data but may have moderate uncertainties. |

| 0.1 – 0.3 | Weak | Suspicious pair; discrepancies in either motion or distance suggest a chance alignment. |

| < 0.1 | Unlikely | No physical association; the stars are very likely independent field stars. |

When a potential binary is identified, the tool evaluates the gravitational relationship:

Definition of specific energy:

Definition of Escape Velocity:

Substitution:

Final equation:

Definitions:

This chapter describes auxiliary functions used in the analysis of stellar kinematics and physical association. These functions support the main astrometric routines and provide derived quantities and comparison metrics.

This function converts the stellar parallax into distance, expressed in parsecs and light-years, including the propagation of the parallax uncertainty.

The calculation follows the standard astronomical relation between parallax and distance and assumes Gaussian error propagation.

where

The uncertainty is derived using standard Gaussian error propagation.

with the conversion constant

Calculates a conservative lower bound of the projected physical separation between two stars by evaluating the projected separation at the distance of the nearer component.

where dnear is the smaller of the two distances and θ is the angular separation in radians.

Returns: projected separation in parsec

This function calculates the absolute magnitude of a star from its apparent Gaia G-band mean magnitude and its distance in parsecs. The uncertainty of the absolute magnitude is derived using the exact propagation of uncertainty, correctly accounting for the logarithmic dependence on distance.

where

This expression uses exact error propagation, taking into account the logarithmic dependence on distance.

Computes the absolute angular difference between two proper motion position angles, normalized to the range 0°–180°.

Uncertainty:

Computes the absolute difference in total proper motion between two stars.

Uncertainty:

The following auxiliary functions compute absolute differences in tangential, radial, and total space velocity using identical mathematical formulations.

Generic Equation:

Uncertainty:

This formulation applies to:

The magnitude of the vectorial difference between the stars' 3D velocity vectors. Unlike the scalar version, this value accounts for the stars' actual directions of motion. It represents the total relative speed between the two components. The following function computes the 3D velocity difference.

Velocity Component Calculation:

Error Propagation of Individual Components:

Total Velocity Difference (Δvrel):

Final Error Propagation (σΔv):

Nomenclature & Constants

| Symbol | Description | Value / Unit / Definition |

|---|---|---|

| AU to km/s conversion factor | 4.74057 | |

| Radial velocity weighting factor | 1.0 (enabled) or 0.0 (disabled) | |

| Parallax | mas | |

| Proper Motion in Right Ascension (μα · cos δ) | mas/yr | |

| Proper Motion in Declination | mas/yr | |

| Standard uncertainty (Sigma) | Associated error of a variable | |

| Tangential velocity component | km/s | |

| Radial velocity component | km/s | |

| 3D Space Velocity Difference | km/s (Vectorial Difference) |

Estimates the stellar spectral class and temperature using the Gaia BP–RP color index based on empirical color boundaries. The temperatures are derived from data provided by the University of Northern Iowa.

Spectral class | BP-RP Color-Index | Temperature

---------------|--------------------------------------

O: | bp_rp < -0,1 | 50000

B: | -0,1 ≤ bp_rp ≤ 0,3 | 15000

A: | 0,3 < bp_rp ≤ 0,5 | 8750

F: | 0,5 < bp_rp ≤ 0,72 | 6700

G: | 0,72 < bp_rp ≤ 1,14 | 5800

K: | 1,14 < bp_rp ≤ 1,8 | 4800

M: | bp_rp > 1,8 | 3300

------------------------------------------------------

The function returns one of the spectral classes: O, B, A, F, G, K, M.

This is an approximate classification intended for statistical and comparative analysis.

The positions of both components are plotted in a simplified Hertzsprung–Russell diagram (HRD). The positions are derived from their calculated stellar luminosities (see next chapter), expressed in solar luminosities and converted to logarithmic scale, and from their effective temperatures (Teff) as provided by Gaia (plotted as solid circles). The effective temperatures are taken from the Gaia GSP-Phot Aeneas solution based on BP/RP spectra (teff_gspphot) and are likewise converted to logarithmic scale. In case the effective temperature is not available, the temperature is estimated from the color index (bp_rp) measured by Gaia (plotted as open circles). Upper and lower bounds of both luminosity and effective temperature are propagated into logarithmic space to derive symmetric uncertainties for the HRD coordinates.

In addition to the stellar positions, the HRD includes schematic regions indicating the approximate locations of the main sequence, giant stars, supergiants, and white dwarfs. These regions are intended for qualitative orientation within the HR diagram and are based on standard tabulated relations between spectral type and effective temperature, such as those provided by the University of Northern Iowa.

This chapter describes the estimation of stellar luminosity and mass for main-sequence stars based on their absolute magnitude and spectral type. The implemented method follows the segmented mass–luminosity relations presented by Eker et al. (2018), adapted here to broad spectral-type intervals for practical application. The luminosity is derived from the absolute magnitude relative to the Sun. The stellar mass is subsequently computed by inverting the logarithmic mass–luminosity relation.

Luminosity:

The stellar luminosity expressed in units of the solar luminosity where

Given an uncertainty

Mass–Luminosity Relation and Mass estimation:

Eker et al. (2018) describe the mass–luminosity relation for main-sequence stars as a segmented power law:

Here,

"O" => { alpha: 3.96, c: 0.00 }, # High Mass

"B" => { alpha: 3.96, c: 0.00 }, # High Mass

"A" => { alpha: 4.67, c: -0.15 }, # Intermediate Mass

"F" => { alpha: 4.67, c: -0.15 }, # Intermediate Mass

"G" => { alpha: 5.56, c: -0.03 }, # Low Mass

"K" => { alpha: 4.20, c: -0.20 }, # Ultra-Low Mass

"M" => { alpha: 2.27, c: 0.60 } # Ultra-Low MassThe Double Star Calculator – Orbit Determination processes historical measurements of the separation and position angle of a double star and attempts to determine its orbital elements.

The Optimization Summary provides quantitative measures describing the quality, robustness, and statistical consistency of the orbit determination based on the supplied observations and measurement uncertainties. It should be interpreted as a whole. Individual metrics are most meaningful when considered together, particularly in relation to the number of observations, the orbital phase coverage, and the assumed measurement uncertainties.

Number of observations used in the orbit determination. Each observation consists of a measured separation (ρ) and position angle (θ), contributing two residuals (x and y) to the fit.

Time interval covered by the observations, given by the minimum and maximum observation epochs. A larger time span generally improves orbit determination, especially for long-period systems, as it increases orbital phase coverage.

The total chi-squared value of the fit, defined as the sum of squared, uncertainty-weighted residuals, where (x, y) are the Cartesian coordinates derived from the separation and position angle, and σx, σy are the corresponding propagated uncertainties. χ² measures the overall disagreement between the model and the observations. In this implementation, χ² is calculated from normalized Cartesian residuals.

Number of independent residuals available to evaluate the fit after accounting for the fitted model parameters. For N observations and seven fitted orbital elements (P, a, i, Ω, T, e, ω), the degrees of freedom are given by the equation below. A positive and sufficiently large number of degrees of freedom is required for a meaningful statistical interpretation of χ² and reduced χ².

The reduced χ² indicates how well the orbital model matches the observations relative to the assumed measurement uncertainties.

Root-mean-square (RMS) residual of the separation (ρ), calculated from the differences between observed and modeled separations. This value quantifies the typical deviation of the observations from the model.

Root-mean-square (RMS) residual of the position angle (θ), calculated from the differences between observed and modeled angles. The RMS position angle is given in degrees and reflects the typical angular discrepancy between the model and the observations.

Maximum absolute residual of the separation (ρ). This value highlights the largest individual deviation between an observed separation and the corresponding model prediction.

Maximum absolute residual of the position angle (θ). This value highlights the largest individual deviation between an observed position angle and the corresponding model prediction.

Fraction of the orbital period covered by the observations, where P is the fitted orbital period. Values close to or exceeding one full period generally provide stronger constraints on the orbital elements, while smaller values indicate limited phase coverage and potential parameter degeneracies.

www.stella-vega.de